Spotlight: Winston Branch

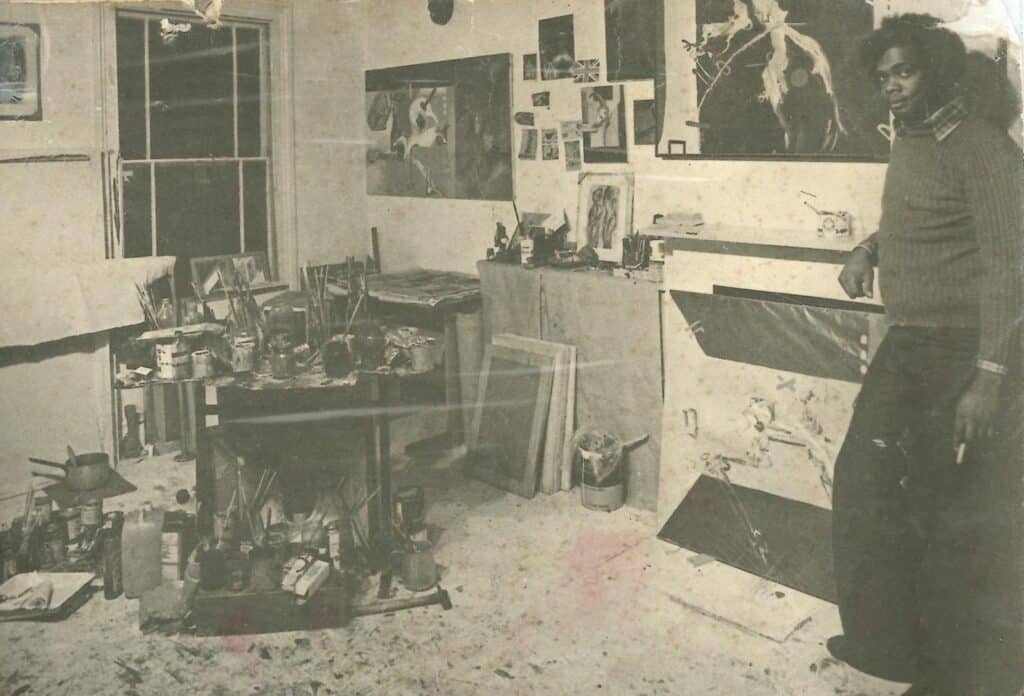

As part of Wandsworth Art’s Black History Month programme, which celebrates and honours work by local Black artists, writers and community leaders, we admire some of the paintings celebrated artist Winston Branch produced when he had his studio at 47 Tyneham Road in Battersea between 1967 and 1976. His work is held in collections at the Tate, the V&A and the British Museum, among many others.

Winston Branch was born in 1947 and raised in Castries, St Lucia until 1958 when his family, who recognised his talent, sent him to England to study art aged twelve. The transition from a tropical Caribbean island to the pace of drizzly London life must have been a shock to the system. Branch has said, “I had to repress my childhood—to forget it as much as possible. I didn’t want to live a divided life so I had to forget the past.”

No one in his family painted, and it took all his courage to stick to his career choice. However, once he had seen the influential work of the Cuban artist Wifredo Lam and Chilean abstract expressionist Roberto Matta, Branch was assured that someone from his part of the world could succeed.

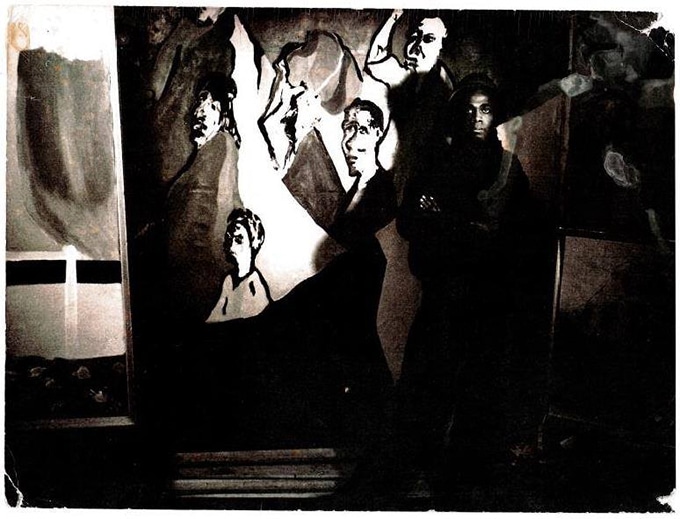

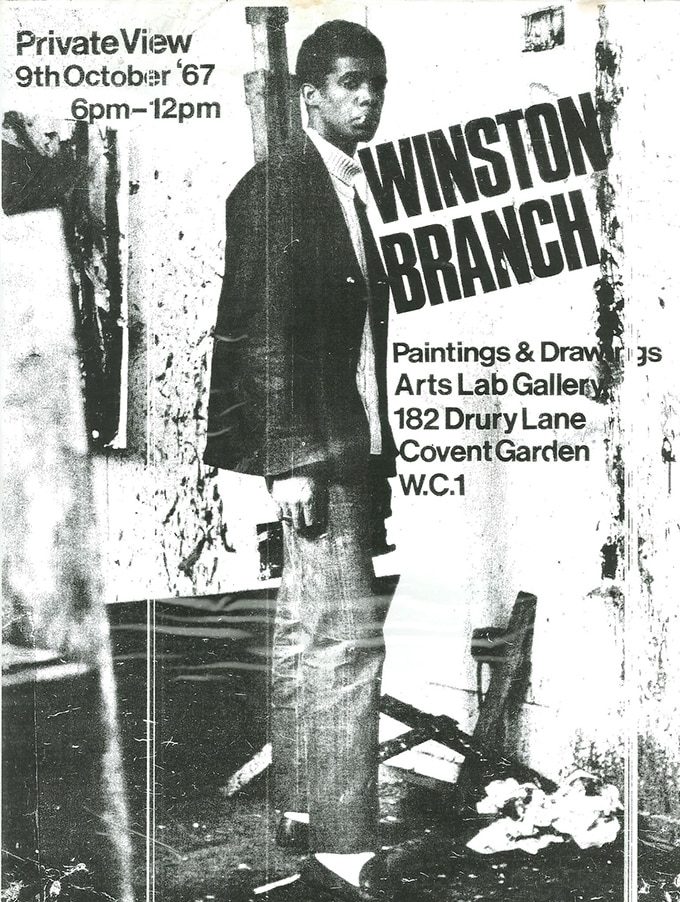

Aged 19, he went to the Slade School of Fine Art, where he studied under Frank Auerbach. Branch was also a member of the The Caribbean Artists Movement (CAM) (1966–72), which was set up by diasporan artists to celebrate a new sense of shared Caribbean ‘nationhood’, exchange ideas and forge a new Caribbean aesthetic in the arts. It was an exciting moment to be an artist in London, a time of radical social change, rebellion and artistic experimentation.

Shortly before graduation in 1970, at the tender age of 24, Branch was awarded the prestigious Prix de Rome, a two-year scholarship to the British School of Rome. He found Rome too provincial and came back to the buzz of London early, and began to teach at Goldsmiths College.

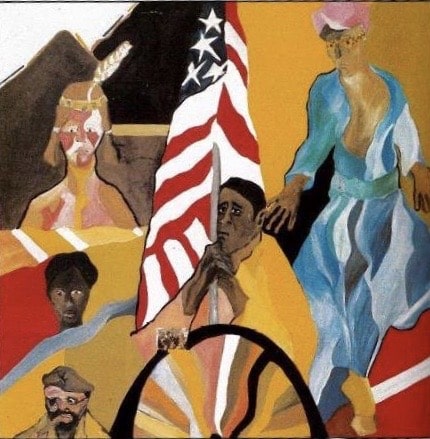

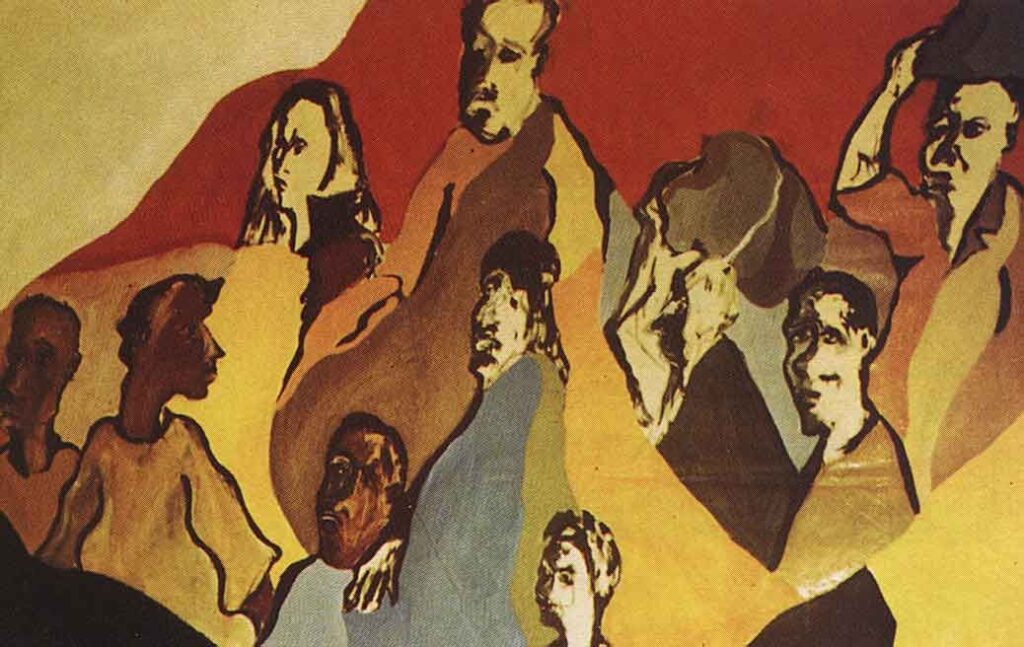

Even before he graduated he was already exhibiting internationally at high-profile institutions and culturally significant arts festivals. In 1969, his paintings were shown at the Pan-African Cultural Festival, where 4,000 painters, poets, photographers, musicians and intellectuals transformed the streets of Algiers into a meeting place of creative culture that united various liberation movements in Africa. In 1971, he had a solo show at the Museum of Modern Art in São Paolo, Brazil, which Branch considers the “second most important venue in the world for contemporary painting.”

While Branch is probably best known for his abstract painting, his portrait West Indian (1973) stands out as a marked exception, and was included in the No Colour Bar exhibition at Guildhall Art Gallery in 2015. Against a background suggestive of colour field painting, a bobble-hat wearing Caribbean man looks out. Branch has recently shared the backstory of this much-loved work:

“The painting came about as a kind of reflection of a journey in Hamburg. It’s very interesting to think about, living in a turbulent time of immigrants, and migration. I went with a friend on a Friday, and I saw all these young black men, handsome, beautiful, semi-drunk, at the train station. And they were huddled together. And I asked my friend, ‘why are these black people, where are they going and why are they drunk?’, and they said ‘well, they are kind of having a nostalgic epiphany, of going back home.’ And I said, ‘but there are no boats, at the train station, and they come from Africa. And they can’t possibly go to Africa on a train.’

I went away, and I didn’t think anything more of it. And I came back to London … and I decided to revisit what I had seen… I [originally] called it Bahnhof. And my dear friend who made the purchase of this painting said no, we’re not calling it Bahnhof, we’re calling it West Indian. And I didn’t want to quibble about the title, because to me it doesn’t make any difference.”

Winston Branch speaking to Art UK

These early representational works, West Indian (1973) and Ju Ju Bird No. 2, (1974) gained him critical attention but these would prove to be the first steps towards a style his name would become known for: abstract landscapes of electric, sensuous colour that move across space and plunge into it, a visual language where forms occasionally merge into the shape of something familiar but otherwise express what Branch calls his ‘inner vision’. After several years of figurative painting, Winston Branch became frustrated that representational images were too easily reduced by the viewer’s interpretations and he became increasingly preoccupied with exploring abstraction: “Since I had no political agenda, [by the mid seventies] I wanted to give painting an autonomous quality, and get away from using it to portray symbols in the natural world.”

In 1976 Branch left London and moved to Berlin for five years on a residency, where he was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship and soon relocated to New York. In 1977, he participated in Festac ’77 in Lagos, an influential and historically significant festival of arts, music, dance, literature and culture that some regard as a turning point in the development of a black global consciousness.

By 1985 he was back again in London and has hardly stopped moving, in life or work, since. In 2018, Tate acquired its first work by Winston Branch, who is now in his 70s and still painting daily.

Sources:

http://www.winstonbranch.com/chronicles.shtml

http://www.lawrence.com/news/2000/nov/09/inner_vision/

https://artuk.org/discover/stories/winston-branch-on-ju-ju-birds-and-never-staying-still

http://new.diaspora-artists.net/display_item.php?id=260&table=artists

https://www.caribbean-beat.com/issue-16/winston-branch-precarious-life-art#ixzz6cAhpZVIJ